My First Semester Studying a Master’s in Sports Training in Football: Experiences and Reflections Across Academia and Adventure in Northern Portugal

On the first day of March, I hastily walked over Ponte Luís and to the university, a petit and refurbished church, where education would be the center of my routine for the following four months.

Porto, Portugal — As the rounds for admission into the master’s program are reopening for the 2024/2025 academic year, I am writing this article about my trajectory and experiences as my Transatlantic move for higher education and a career coaching professional football has become further unlocked and defined.

With more than a handful of years in football scouting from a compilation of experiences visiting and working in European football academies and scouting trips to Portugal’s Alentejo and Algarve regions, I sought to pair practical experience with institutional education.

In August of 2023, I submitted an application in the latter rounds of the admission process to the Lusophone University of Porto for their Sports Training in Football master’s program, which also gives equivalency to UEFA(Union of European Football Associations)-B coaching certification.

Admitted to the university in early September with a late September start, I immediately asked course director, Dr. Filipe Casanova, to defer my acceptance until the spring to best prepare myself for this step before stepping into this large life-transition.

When I arrived in a cold and damp late February, I quickly recognized that I was perhaps the first North American to be enrolled in the coaching program at this university. Additionally, I am likely the first person of Mexican and El Salvadoran descent to be in the university.

With proficiency in the Portuguese language coming from my accumulated eight months of being in Portugal over 8 years and a six-month fluency course proctored by Instituto de Camões, confidence became my beacon to ask questions in a variety of seminaries such as “Talent Selection and Development”, “Sports Agency”, or “The Football Coach As an Integral Part of Different Cultures” among other topics.

Although English is spoken quite well in Portugal and there was a non-Portuguese speaker in the course, I challenged myself in my first semester to speak as much of the home language as to develop a working function.

To become a UEFA-B certified coach through the pathway offered by the university, a working understanding and comprehension of football-applicable physiology and physiotherapy were made the focal points. With a political science educational background, and not one in human anatomy, I was faced with a small challenge in absorbing the importance of ATP and CK, chemical reactions with enzymic variables, and many other biological components that can make for molecular and marginal preconditions to prepare a high-performance football team to have as much of a competitive edge as possible.

Recruited by Dr. Filipe Cassanova, classes ranged from communications, audiovisual, and media production, management, organization, observation, and analysis, to the spectrum of seminaries taught by practical experts, and leaders by profession.

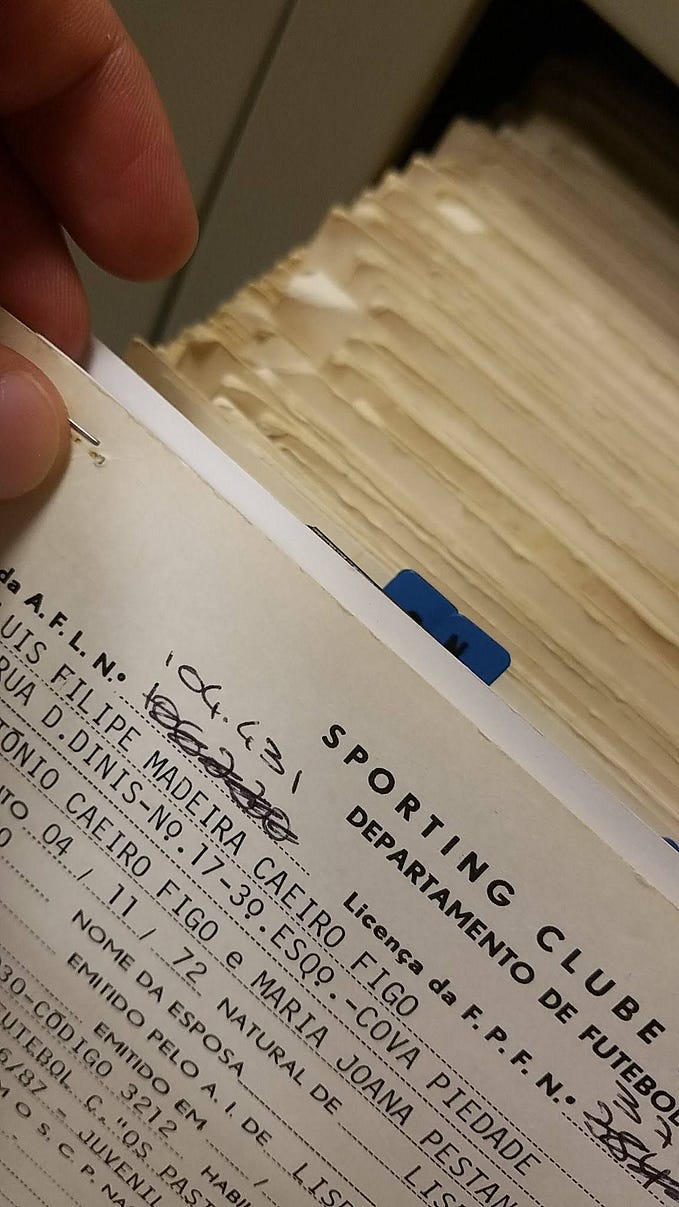

Coming from the United States with a USSF(United States Soccer Federation)-D License was not enough to fill the appetite of the course’s requisite to have a UEFA-C license, so upon arriving, I looked for a course and enrolled in the high-intensity and short-duration UEFA C course offered by the Football Association of Vila Real. Situated in the northern interior of Portugal, my course commute was a lengthy hour and ten minutes from Porto.

In Vila Real, I learned that the UEFA-C encompassed the base of football coaching in the amateur and academy football context in Europe with a regionally focused perspective capable of being applied in many contexts: Methodology of Training, Motor Capacities, Technical-Tactical, Psychology Applied in Football, Management, and Organization, each taught respectively by a professor-expert.

Once completing this two-month-long intensive course, most coaches, and myself included, are expected to begin their internship to complete the UEFA-C requirement. At the end of this first internship (that my second and final semester of university lectures will pair with), I will then be able to do the UEFA-B license internship, where once again, I will have to work with a football club for about 10–12 months.

The Union of European Football Association’s governance of football and de facto regard as the premier football coaching authority in the world was the primary motive to relocate to the European continent. However, while in Portugal, there have been many other available and interesting “side quests” that I incorporated as a part of my journey to increase my knowledge of football coaching and scouting from grassroots to professional levels.

While adventures do not supplement my degree or certification, networking and familiarizing myself with a new environment are paramount to achieving success. At times, however, I have asked myself, “Am I doing too much?”

The master’s program became the galactic center and my “side quests” were my spirals. My way to coaching certification, visits and presentations hosted by professional football clubs and federations with participants ranging from grassroots coaches to FIFA and UEFA officials such as the Applied Science in Football conference hosted by the Portugal Football School in May made my academic learnings pop out and linger for longer in my brain.

With so much sensory data to absorb from different areas, I struggled, yet managed to maintain focus on time management and use time to perfect what assignments and exams were needing attention. This is the charm of applying your experience.

It sounds simple, but the practice of sending a thought to your unconscious for it to come back to your conscious is at times an obstacle in itself.

Raymond Verheijen and anyone on his 2024 early-summer tour to Istanbul’s Galatasaray, northern Portugal’s Sporting Clube de Braga, and Spain’s Sevilla Futbol Club 6-day courses would know.

In what was at times a battle with my brain to think and deduce reasoning from logic questions, the course I attended in Braga to participate in the 6-day course was the cherry on top of my first four months in Portugal as it merged a country I have a strong affinity for with references that I have used to make the improvements (or “changes”) I needed to get closer to personal fulfillment.

When the course ended, Raymond shared advice with me regarding my courseload, “Go slow”. Ironically, this has still been the opposite of what I have been doing, but when the precursor of burnout began to hit in the storm of a busy June, I began to understand.

The wave of missed lectures, assignments, and novelties piled up on me. Rather than doing them ahead of deadlines, I started working on them on deadline day. This reminded me of when I last experienced brain overload and subsequent burnout like when I was a Cal Berkeley student.

Thankfully, my professors understood late assignments and I internally nominated myself to be the “2nd worst student” in the world as a joke to keep my brain up. Furthermore, it was a moment where I began to acknowledge the vast information intake I’ve had since switching my life routines in March from supermarket clerk to postgraduate student.

Now, in late July, just a few days before my birthday and following my annual “one article a year” quota, I wanted to end this reflection with a journal confirming the effects of academia on the student’s brain.

One of the invited speakers to the Lusophone University of Porto was Sixto González-Víllora who recently released an article titled, “Autorregulación del aprendizaje y lectura científica en docentes en formación. Un estudio exploratorio”. In English, it means the autoregulation of learning and scientific study for teachers in development.

As a teacher (specializing in coaching football) pursuing education myself, I learned that academia presents a higher cognitive load on the brain. Specifically, academia requires some measure of independence to learn, self-regulation, and self-direction to achieve success.

Self-regulated learning requires a cognitive and metacognitive process that is motivated and paired with emotion. Noticing smaller objectives on the road to a larger one, the selection of strategies, and the cognitive recognition of performance and the attained objectives have also been conducive to increased academic performance.

As to conclude, according to the study published by an invited speaker whom I met while in my first semester, I have done a lot: I finished an eventful and cognitively challenging first semester in Portugal with decent marks, new connections, and familiarity with what is now around me despite the challenges of being in a new city, embarking on a mission that I’ve yet to meet another one on.

Between switching careers and countries, completing three different coaching courses, and traveling to different corners of Portugal to scout promising talent or visit conferences, I rest my laurels as I know that perhaps, the most challenging part of my Transatlantic transition into higher education is for the most part, over and complete.